One of the untold stories of cinema is how the Guns of Navarone was nearly shot in Cyprus, as was an abandoned Kenneth More epic on the EOKA struggle. However, as Nathan Morley reveals, a young British soldier did manage to reach Hollywood, thanks to a kiosk in Larnaca…

In the past year or so, as I’ve toiled on a biography of British film star Jack Hawkins, Cyprus – for one reason or another – kept cropping up during my research. From Kenneth Williams and Gilbert Harding to Peter Sellers and Tommy Cooper – all have a connection to the island. For example, few people know it, but Cooper was married in Nicosia in February 1947, and honeymooned at the Savoy Hotel in Famagusta, an evening his bride later described as ‘Bloody wonderful’.

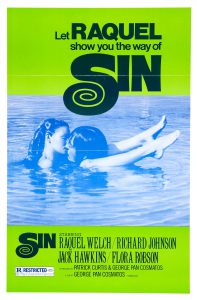

I’m rambling. Let’s get back to Jack Hawkins, the rugged star of epic such as The Cruel Sea, Zulu, Ben-Hur, and The Bridge on the River Kwai. In 1970, he flew to Nicosia International Airport to join the cast of Sin, an exciting feature designed to place Cyprus on the movie map. Photographed at the now derelict arrivals hall wearing light blue flannel slacks, a beige button‐down shirt, and clutching a briefcase, he was hardly an obvious choice for the part of a Cypriot village priest. In fact, only his love of travel can possibly explain why he chose to feature in this American-Cypriot-British drama starring Richard Johnson and the vivacious Raquel Welch, then cinema’s biggest female attraction.

Patrick Curtis, Welch’s husband – and producer – labeled the project a ‘modern drama with Greek tragedy overtones’, whilst Hawkin’s wife, Doreen, described Jack’s part as a ‘bit of an Archbishop Makarios role’. Welch played a married woman in a sleepy Cypriot village embarking on an affair with a friend of her husband, and the story had a classically blood-soaked ending. ‘This is the first time I’ve had the opportunity to play a real live woman, a woman of the earth—not just a celluloid character,’ Welch enthused.

The love scenes, she said, were the most sensual she’d ever played. As the project gained steam, Curtis hastily arranged shooting in the Greek Cypriot village of Karmi during the blistering August of 1970. In preparing for the part, Jack spent several days watching the priest at the church of the Virgin Mary in the village square.

By this point, he had lost his voice to throat cancer, but along with Dame Flora Robson, playing Welch’s mother, they enjoyed a rapport with the starlet and embarked on a PR circus, which literally stopped the traffic in Nicosia when fans held up pads for autographs near the Presidential Palace. Famed for playing military types, Jack even croaked his way through a BFBS interview. At the Dhekelia officers’ mess, he was treated with a reception befitting a military dignitary.

There were great hopes for Sin, but sadly, it was greeted with incredulity and disappeared without a trace, except for grainy VHS rips floating around online. To say that nobody watched it is an understatement. Curtis did try to resurrect the movie by changing the title, twice. In both cases he failed. There are no box office revenue figures, and details of distribution remain sketchy. In fact, I’ve never met anyone who has seen it.

On a recent afternoon, when discussing Jack Hawkins with Peter Medak – who, funnily enough, directed Peter Seller’s flop Ghost in the Noonday Sun here in Cyprus, ‘the most stressful project of my entire life’ – we got discoursing about Kenneth More, another veteran British actor. More, it seems first took an interest in Cyprus in 1959 when Carl Foreman, writer of The Bridge on the River Kwai, was assembling a top line international cast for The Guns of Navarone, about a heroic band of Allied saboteurs attempting to blow up a massive gun on a Nazi occupied island in the Aegean. Gregory Peck and Anthony Quinn were booked, whilst there was even talk of Maria Callas joining the team.

Remarkably – as confirmed by newspapers at the time – Foreman met President Makarios in Nicosia to discuss using the island as a location. Cape Greko, the impregnable cliff near Ayia Napa, was even muted as a possible backdrop for the dramatic action scenes. This I know, because my friend the late author Barry Wynne, a long-time resident of Larnaca, famed for his screenplay The Curse of King Tut’s Tomb, had firsthand knowledge of the saga.

However, the toughest problem to be tackled was that of keeping the stars safe. And, after much back and forth, filming eventually took place in Rhodes, as Cyprus was still considered too dangerous. ‘Pity,’ Wynne lamented, ‘Could you imagine what it would have done for tourism…Gregory Peck and David Niven descending down Cape Greko on a rope in glorious technicolor?’ Indeed, especially as it was the second top-grossing film of 1961.

In the end, Kenneth More never appeared in Navarone but was later offered the lead in The Cyprus Story, a gripping drama about EOKA’s fight for freedom. This little-known project was to be produced by British Lion, one of the major studios in London, which tapped Harry Andrews, Elsa Martinelli and Herbert Lom for leading roles. On screen, Kenny was to have a romance with Martinelli, playing the daughter of an EOKA sympathizer.

Excited about appearing in such a serious drama, More said his character was not a typical stiff upper lip officer. ‘He makes a nuisance of himself. He has a lot to say about the sort of treatment meted out to the Cypriots.’ As the project gained steam, writer Jack Pullman arrived in Nicosia to interview Cypriot leaders, British troops, government officials, and people caught in the conflict. ‘We have got the cooperation of the army,’ Kenny explained.

‘The Cypriot authorities wanted one or two changes in the script. In a few instances they thought we were being a little too kind to them and a little too harsh to ourselves.’ However, as Carl Foreman had earlier discovered, Cyprus continued to endure very real political problems. And when a shaky peace– erupted into sporadic clashes and gunfire – work on The Cyprus Story abruptly folded. A similar EOKA themed project, The High Bright Sun starring Dirk Borgade was filmed a few years later in Italy, which – given the local troubles – stood in admirably for Cyprus.

Without a doubt, Oscar-winning composer John Barry’s brush with Cyprus was more productive. As a conscript – he seemed oblivious to the EOKA struggle during his National Service at a camp near Larnaca, ‘where there was nothing to do except go to a local village and get drunk, so I sat in the storehouse with a piano for sixteen months and taught myself arranging.’ No mean accomplishment.

But then – courtesy of the Larnaca post office – he embarked on a correspondence course with American jazz musician Bill Russo. ‘There was this guy who had one of these shops that sell ashtrays and things with maps on them. I used to go in once a week, with my army pay, buy the dollars, put the cash in an envelope and send them to Bill in Chicago’. Inevitably, he formed a band playing exclusively at the Naafi hut, which I think, sat at the entrance of the old Pergamos camp – now a deserted lump of land near Pyla.

After leaving Cyprus, it didn’t take long for him to find his due as an important musician. Barry went on to write scores for Hollywood blockbusters including The Ipcress File, Zulu, Midnight Cowboy, and eleven James Bond films.

I’m digressing. Though Kenneth More was disappointed at the cancellation of The Cyprus Story, he brought his girlfriend Angela Douglas to the island for a holiday during 1962. After checking-in to the Dome Hotel on the northern coast, they embarked on three weeks of romantic dinners, exploring in a hire car, and bathing in the Mediterranean. One afternoon, a local reporter – notebook in hand – caught him in faded blue jeans and trainers spending a day in Famagusta meeting an old friend from his Royal Navy days, ‘and he called only at the Ship Inn and the Acteon Beach Restaurant where he enjoyed a meze’.

In his memoirs, Kenny remembered having a wonderful time sunbathing on deserted beaches. ‘There were few guests at the hotel and the only other Britisher was a woman who always ate on her own. We never saw her at the beach’. By this point, celebrity sightings in Cyprus were commonplace. In fact, Kenneth Williams – that star of the Carry On’s – didn’t even get a mention in the press during his visit in the early 70s. It seems perfectly fitting – given his difficult personality – that he snottily confided in his diary that he hated the holiday and was repeatedly ‘pestered’ to buy property in Limassol. He didn’t and never returned.

Incidentally, for the full story of Peter Seller’s disastrous attempt to make a film in Cyprus, look out for the marvelous documentary ‘The Ghost of Peter Sellers,’ produced by Paul Iacovou.

Jack Hawkins: A Biography by Nathan Morley will be published in October 2024.